By Emily Heisinger A while ago, people around the world acknowledged October 10th as “World Mental Health Day.” Many businesses and organizations reached out on their social media sites, hoping to spread the word and to welcome the conversation into their day. I saw many of my friends from junior high post on their Facebook pages, saying things like “you can always call me”, “please don’t be silent about it”, and most used: “you are not alone”. What I found concerning was that not very many of my Christian friends and family members shared these messages.

A while ago, people around the world acknowledged October 10th as “World Mental Health Day.” Many businesses and organizations reached out on their social media sites, hoping to spread the word and to welcome the conversation into their day. I saw many of my friends from junior high post on their Facebook pages, saying things like “you can always call me”, “please don’t be silent about it”, and most used: “you are not alone”. What I found concerning was that not very many of my Christian friends and family members shared these messages.

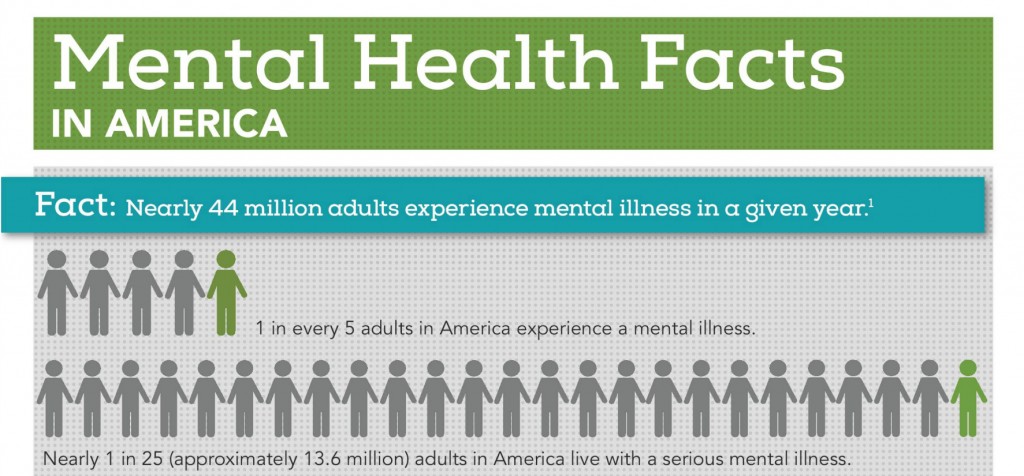

A shocking statistic given by the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) state that one in five adults in America experience a mental illness at some point in their life. 25% of this is represented by those who struggle with major depression or an anxiety disorder. These numbers are…huge. This statistic easily supports the idea that we all know someone who is struggling with a mental health issue.

NAMI also reports that in the last year, 60% of adults, as a group, did not receive any kind of mental health service. If we factor race into this statistic, NAMI reports this:

“African American & Hispanic Americans used mental health services at about ½ the rate of whites in the past year and Asian Americans at about ⅓ the rate”.

Have you noticed someone in your relational circle suffering from mental illness? What is your first instinct or reaction?

Sometimes, the Christian community finds it difficult to talk about things like anxiety and depression. We tend to brush it off or avoid talking about it all together. There is a tendency towards secrecy and withdrawal from the subject.

I have been trying to grasp what it is that makes it so uncomfortable to discuss mental health issues and welcome them into our church communities. What drives the avoidance? I wonder if it is driven by the fact that historically, the church considered mental health issues somehow related to sin, or a following of the wrong path in life. Maybe we consider the responsibility of care and intervention to be solely on the medical community?

I also wonder if it is out of fear. Michelle Willingham, who is a professor at Biola University and a psychologist, once said during her speech on mental health at a campus chapel, “What we do not understand, we fear.” Do we simply have a lack of understanding of mental illness, and therefore a fear of approaching it as a subject of conversation?

As I contemplate these questions, I wonder if it is possible to realign our thought-process surrounding the mental health care issue. What if, no matter the reason, when we see a person struggling, we join them in their struggle, recognizing their experience of difficulty, and putting aside our pre-conceived notions and judgments to offer support that is loving and kind?

Ephesians chapter 4 talks about unity in the body of Christ:

“As a prisoner of the Lord, then, I urge you to live a life worthy of the calling you have received. Be completely humble and gentle; be patient, bearing with one another in love. Make every effort to keep the unity of the spirit through the bond of peace. There is one body and one spirit- just as you were called to one hope when you were called- one Lord, one faith, one baptism; one God and Father of all, who is over all and through all and in all.”

In the model of the church set before us in this passage, the body is instructed to take steps to maintain their unity and love for one another by supporting those who suffer among them. Supporting a suffering member with gentleness and patience is an opportunity to live in true agape love.

On her blog, Kay Warren of Saddleback Church in Southern California writes about her vision for how mental health fits into the church. For her, it’s about being open and aware that it exists and then being loving and vulnerable with one another. She writes this:

“When people hear the story of somebody who looks similar to them, and can go, “Wow! If she’s living with that or she’s experiencing that, maybe I’m not so weird after all.” It allows these “me, too” moments that increase fellowship, that increase unity, because people are not living in fear and feeling all alone. In reality, there are some problems that come along with being really honest and vulnerable about your own life, but I would rather live with the awkwardness of freedom and honesty than the awkwardness of secrecy.”

In reality, mental illness in the church is another opportunity for the people to be in unity, and to grow in love for one another. Perhaps think back to that person you identified in your relational circle. How great it would be for them to continually experience an Ephesians 4 love and unity, that is full of “me too” moments.

Leave A Comment